How to Read Blues Music Notes

Contents

A step-by-step guide to reading blues music notes, so you can finally understand what you’re playing (or what someone else is playing).

The Basics of Reading Music Notes

If you want to learn how to read blues music notes, there are a few things you need to know. First, you need to be able to identify the different notes. The notes in music are A, B, C, D, E, F, and G. You will also see sharps and flats, which are notes that are a half step higher or lower than the regular notes.

learning the staff

When you’re ready to start reading music, you need to know how to read the staff. The staff is the foundation of written music, and once you know how to read it, you can begin learning to play your favorite songs.

The staff is made up of five horizontal lines and four spaces. The spaces represent the notes F, A, C, and E. The lines represent the notes G, B, D, and F. These notes are also known as “natural” notes because they are not altered by accidentals (sharps and flats).

To remember which note corresponds to each line and space on the staff, use the mnemonic device “Every Good Boy Does Fine” for the lines and “FACE” for the spaces.

Once you know which note corresponds to each line and space on the staff, you can begin to read music. Notes are represented by symbols called noteheads, and they can be placed on either a line or a space. The notehead is usually black, but it can also be white (called a whole note) or filled in (called a black note).

Notes that are higher than middle C are written on dots called ledger lines. You can add as many ledger lines as you need to write any pitch. Just remember that ledger lines above the staff go up in pitch (higher notes) while ledger lines below the staff go down in pitch (lowerNotes).

learning the notes

When you’re first learning how to read music notes, you need to start by learning the basic symbols for the notes. In music, there are only twelve notes: seven natural notes (A, B, C, D, E, F and G), and five accidentals (sharps and flats). Each one of these notes can be represented by a specific symbol.

The note A is represented by a circle with a line through it: A. The note B is represented by a circle with two lines through it: B. The note C is represented by a circle with a line through it and a dot above it: C. The note D is represented by a circle with two dots above it: D. The note E is represented by a circle with a line through it and three dots above it: E. The note F is represented by a circle with four dots above it: F. Finally, the note G is represented by a circle with a line through it and five dots above it: G.

Now that you know what the basic symbols for the notes are, you can start learning how to read music notes on the staff.

More Advanced Music Notes

learning about sharps and flats

Most music is based on the major scale, which consists of seven notes. The eight note of the scale is called the octave, and it’s just a repeating of the first note an octave higher. Each note in between the octave is named after the first seven letters of the alphabet: A, B, C, D, E, F and G.

If a song is in the key of C major, that means that C is the root or starting note. The other notes in the C major scale are D, E, F, G, A and B. You’ll notice that there are no sharps or flats in between these notes – they’re all natural notes.

However, there are 12 notes in total in music (A-G plus the octave), so we need to find a way to add sharps and flats to fill in those gaps. If a sharp (#) is placed before a note, it means to play that note one half step higher. For example, if there’s a sharp symbol before an E on your sheet music, you would play F instead. If a flat (b) is placed before a note, it means to play that note one half step lower. So if there’s a flat before an E on your sheet music, you would play Eb instead.

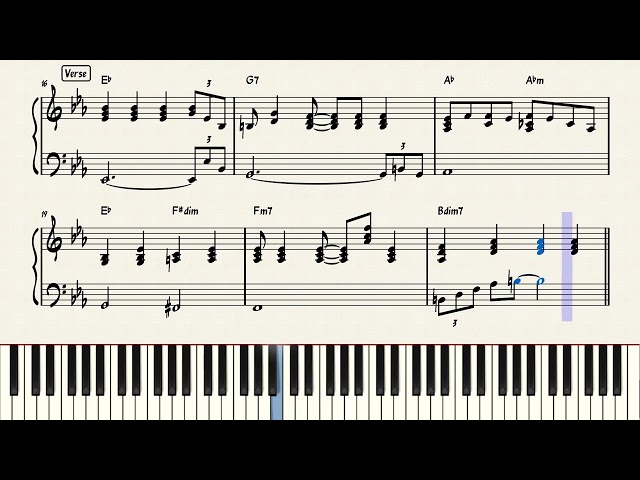

learning about chords

In music, a chord is simply two or more pitches sounded together. Chords can be created with any combination of notes, but some will sound better than others. The simplest chords are made up of just two notes — we call these dyads — while more complex chords can have four or more notes.

In order to create chords, we need to understand intervals — the distance between two pitches. When learning chords, it’s helpful to think about interval stacks. An interval stack is simply a series of intervals that are played one after the other. For example, a major chord is made up of the intervals 1-3-5 (the first, third, and fifth notes in a major scale).

We can use this information to build any type of chord we want. For example, a minor chord is made up of the intervals 1-♭3-5 (the first, flat third, and fifth notes in a major scale), while a seventh chord is made up of the intervals 1-3-5-7 (the first, third, fifth, and seventh notes in a major scale).

Blues music often uses seventh chords, so it’s important to learn how to build them. To build a seventh chord, we simply add another interval to our stack — in this case, the seventh note in the scale. For example, a C7 chord would be made up of the pitches C-E-G-B♭ (the first, third, fifth, and flat seventhnotes in the C major scale).

As you can see, learning how to build chords is simply a matter of understanding intervals. Once you know how to stack intervals on top of each other, you can create any type of chord you want!

Even More Advanced Music Notes

So you know some of the basics of reading music notes, but you’re ready to tackle something a little more challenging? In this section, we’ll cover some more advanced music notation, including how to read chords, embellishments, and more.

learning about time signatures

In music, a time signature tells you the meter of the piece you’re playing. In other words, it tells you how many beats are in each measure and what kind of note gets one beat.

The top number in a time signature tells you how many beats are in a measure. The bottom number tells you what kind of note gets one beat. For example, in 4/4 time, there are four beats in a measure, and a quarter note gets one beat. In 3/4 time, there are three beats in a measure, and a quarter note gets one beat.

Time signatures are important because they tell you the rhythm of the piece you’re playing. They also tell you how to count the beats.

There are many different time signatures, but some of the most common are 2/4, 3/4, 4/4, 6/8, 9/8, and 12/8. These time signatures are all used in blues music.

2/4 time is sometimes called march time because it is often used for marches. In 2/4 time, there are two beats in a measure and a quarter note gets one beat. Here is an example of 2/4 time:

One two Three four Five six Seven eight

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

do re mi fa so la ti do do re mi fa so la ti do

C D E F G A B C C D E F G A B

learning about key signatures

As you become more familiar with reading music, you’ll encounter something called a “key signature.” A key signature is a symbol at the beginning of a song that denotes which notes will be sharp or flat for the rest of the song.

There are only twelve major and minor keys, so once you learn them, you’re set! To make things even easier, key signatures follow a very predictable pattern. If a key signature has one sharp (#), it will always be F#. If it has two sharps, they will always be F# and C#. Three sharps are always F#, C#, and G#.

To figure out the order of sharps in other keys with more than three sharps, just remember the phrase “Father Charles Goes Down And Ends Battle,” where “Father” is F, “Charles” is C, “Goes” is G, etc. The only flat key signatures are Bb and Eb; everything else has at least one sharp.

Now that you know how to read key signatures, understanding blues music notes will be a breeze!